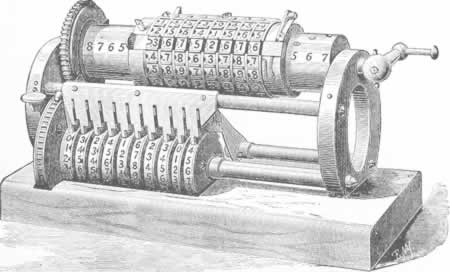

Back in July, Tim O’Reilly posted about his What’s the Future (WTF) Conference, which is this week. O’Reilly’s article paints a picture of the world upended and transformed, hardly familiar. He then writes, “The algorithm is the new shift boss.”

That shivers me timbers. I’m truly not cynical, but those are heavy words and unintended consequences being what they are, we must consider the bad with the good. O’Reilly wants to start a dialog about technology and the future of work. The first comment below his post from middle school French teacher, Léa Dufourd, reads: “When the ticket to go to the conference costs $3500, you already have a good idea at least of who is invited to think and design the future of work… WTF?”

That shivers me timbers. I’m truly not cynical, but those are heavy words and unintended consequences being what they are, we must consider the bad with the good. O’Reilly wants to start a dialog about technology and the future of work. The first comment below his post from middle school French teacher, Léa Dufourd, reads: “When the ticket to go to the conference costs $3500, you already have a good idea at least of who is invited to think and design the future of work… WTF?”

O’Reilly’s response is more or less a defense that he is curating content and inviting people as well as providing discounts; fair enough. He runs all sorts of different events and some are free. However, WTF is specific to the future of work. His other events are not. It’s happening in San Francisco, so after airfare, hotel, conference fees, and food, a trip like that could be $5500 or more. That’s about 10% of the average annual teacher salary.1 For me, that money represents the total amount of work I currently have to put into my aging, but paid-off van.2

The Algorithm Becomes More

Most people who are deeply affected by the issues O’Reilly mentions will never hear of his conference. Those not in the network of people planning, speaking, or attending WTF are excluded. If we don’t mix an already problematic Silicon Valley culture3 with, say, people struggling to pay bills or with chronic illnesses, there is no context for any of the thought, business, and political leaders. They’ll just ride roughshod through the workplace like Donald Trump in a china shop. The Algorithm is the new elitist buffoon.

As a UX conference planner, I see first hand how easy it is for practitioners to stay sealed up in their little tech bubbles. We generally discuss how we work, but how we affect people outside of the user paradigm is a topic starving for attention. We are in such a rush to create addictive user experiences, we hardly notice a large swath of humans do not have access to the same technologies, disposable income, and discourse communities we do.4 The higher the conference price, the more exclusive the group of people. The Algorithm is a product of the ivory tower.

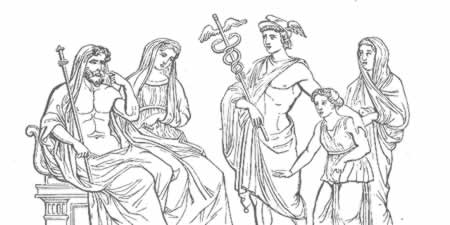

We are losing control over our own lives as technology erodes the perceived need for us. According to the Greeks, circa 1200 BC, the gods of Mount Olympus were prescribers of fate. Some helped, some hindered, and some impregnated, but humans had little if any self-determination. Like the Greek gods, the Algorithm tinkers in our lives and most of us don’t know when or how. It works in the background affecting nearly everyone in the world, but only about 13% of the global population are actual programmers.5 Even among the 18.2 million developers, not everyone truly understands how software works at all levels. The best-of-the-best programmers are with the more affluent business leaders using the most resources; think of them as demi-gods. The Algorithm is a faceless god.

We are losing control over our own lives as technology erodes the perceived need for us. According to the Greeks, circa 1200 BC, the gods of Mount Olympus were prescribers of fate. Some helped, some hindered, and some impregnated, but humans had little if any self-determination. Like the Greek gods, the Algorithm tinkers in our lives and most of us don’t know when or how. It works in the background affecting nearly everyone in the world, but only about 13% of the global population are actual programmers.5 Even among the 18.2 million developers, not everyone truly understands how software works at all levels. The best-of-the-best programmers are with the more affluent business leaders using the most resources; think of them as demi-gods. The Algorithm is a faceless god.

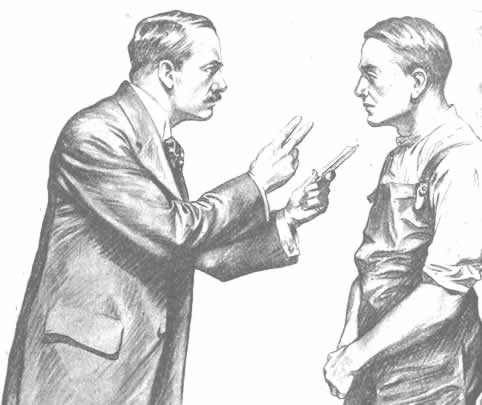

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a human creation. Like any bad code that goes into production, it’s not immune from ignorance. Programmers don’t understand everything about everything and probably don’t have context for what they are creating outside of vague bullet points written by a yuppie in a coffee shop. How does any AI know what productivity is when we can’t define it at the human level (see more on this below below)? Imagine Siri saying, “If you have time to lean, you have time to clean.” The Algorithm is the assistant manager nobody likes.

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Robert Solow, 1987

Most job seekers are unaware their resumes are automatically filtered through applicant tracking systems (ATS). ATS look for keywords in resumes that match open job descriptions using undisclosed algorithms.6 Assuming seekers are aware of ATS, they must rework their resumes for every job or risk spitting into the wind. This is the conversion from HR to Dehumanized Resources; the applicant pool is sifted to eliminate those silly people who can’t meet unexpressed expectations. Nobody gets to meet in real life. The Algorithm is the petty bureaucrat.

Voter tracking databases designed to find voter fraud may have disenfranchised nearly 7 million voters simply because of name matches. Most states participating in the Crosscheck program will not reveal whether or not they purged matches.7 The Algorithm is the autocrat.

There are so many laws on the books, you can argue that ignorance of the law is a constant state of existence.8 We blindly agree to whatever terms of service or disclosure is presented to us because to read and fully understand all of the disclosures we agree to is literally impossible. The more we agree to, the more we give up our constitutional rights.9 The Algorithm houses the infoglut within a cryptocracy.

The rise of computer information technology (IT), in general, has given us the Productivity Paradox, a socioeconomic problem instead of a cool cyberpunk premise. In a book review, Nobel Prize winning economist Robert Solow famously, off-handedly quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”10 Ever since, economists have been working the problem. With knowledge work more fractured and ad hoc than ever, how do you begin to measure productivity when workers are interrupted about 88 times a day?11 When IT budgets are increased to buy into more technology when workers don’t have a handle on their own time, it’s as if the workplace has become a living M.C. Escher painting. The Algorithm is the ouroboros.

People are increasingly acting as if they have disorders, alarming behaviorists worldwide. They show signs of addiction withdrawal and anxiety when separated from mobile phones. Many use online interactions to avoid real life social situations. ADHD-like behavior resulting from living split-screen lives probably doesn’t help the previously mentioned productivity paradox.12 Researchers at Bournemouth University in the UK want warning labels on mobile technology in the same manner as alcohol and tobacco products.13 The algorithm is the pusher man.

People are increasingly acting as if they have disorders, alarming behaviorists worldwide. They show signs of addiction withdrawal and anxiety when separated from mobile phones. Many use online interactions to avoid real life social situations. ADHD-like behavior resulting from living split-screen lives probably doesn’t help the previously mentioned productivity paradox.12 Researchers at Bournemouth University in the UK want warning labels on mobile technology in the same manner as alcohol and tobacco products.13 The algorithm is the pusher man.

Breathless anticipation of the future feels fun and exciting, but like nearly every human invention, there are consequences. I don’t think the new shift boss is completely competent. He’s helpful when the circumstances allow, but he’s also an asshole. Everyone needs to be in this discussion.

Notes

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2013.” Government. National Center for Education Statistics, April 2013. Link. ↩

- I took this same van to see Faith No More recently with my daughters’ school band and lacrosse stickers on the back window. That was so not metal. ↩

- Lobo, Rita. “Silicon Valley’s Sexist Brogrammer Culture Is Locking Women Out of Tech.” Economic News. The New Economy, June 5, 2014. Link.

Raja, Tasneem. “‘Gangbang Interviews’ and ‘Bikini Shots’: Silicon Valley’s Brogrammer Problem.” Mother Jones, April 26, 2012. Link.

Zelle, Art. “Tech Firms Should Drop ‘Brogrammer’ Culture, Welcome Women in.” Economic News. TheStreet, June 8, 2015. Link. ↩ - Warschauer, Mark. Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003. Link. ↩

- Thibodeau, Patrick. “India to Overtake U.S. on Number of Developers by 2017.” Computerworld, July 10, 2013. Link. ↩

- Weber, Lauren. “Your Résumé vs. Oblivion.” Wall Street Journal, January 24, 2012, sec. Careers. Link. ↩

- Palast, Greg. “Voter Purges Alter US Political Map.” News. Aljazeera America, November 14, 2014. Link. ↩

- Husak, Douglas N. Overcriminalization: The Limits of the Criminal Law. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. ↩

- Radin, Margaret Jane. Boilerplate: The Fine Print, Vanishing Rights, and the Rule of Law. Princeton University Press, 2012. ↩

- Solow, Robert. “We’d Better Watch Out, Review of SS Cohen and J. Zysman, Manufacturing Matters: The Myth of the Post-Industrial Economy.” New York Times Book Review 36 (July 7, 1987): 37. ↩

- Wajcman, J., and E. Rose. “Constant Connectivity: Rethinking Interruptions at Work.” Organization Studies 32, no. 7 (July 1, 2011): 941–61. doi:10.1177/0170840611410829. ↩

- Rosen, Larry D. Ph D. iDisorder: Understanding Our Obsession with Technology and Overcoming Its Hold on Us. Reprint edition. St. Martin’s Press, 2012. ↩

- Ali, Raian, Nan Jiang, Keith Phalp, Sarah Muir, and John McAlaney. “The Emerging Requirement for Digital Addiction Labels.” In Requirements Engineering: Foundation for Software Quality, edited by Samuel A. Fricker and Kurt Schneider, 198–213. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 9013. Springer International Publishing, 2015. Link. ↩

Speak Your Mind